Contents

- Rocky Mount, NC

- Audio Tape

- Historical Context (A Brief Overview)

- Significance

- “I Dream a World” by Langston Hughes

- Langston Hughes

- Difficulty in Documenting the Connection

Rocky Mount, North Carolina

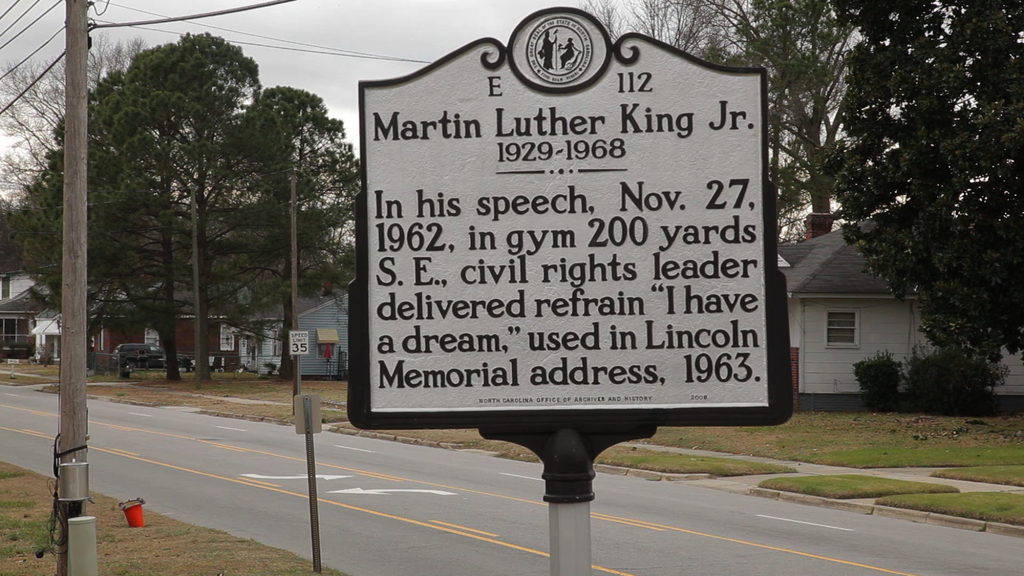

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. first delivered the now famous refrain “I have a dream” in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on November 27, 1962. Dr. King ended his fifty-five minute speech in the Booker T. Washington Gymnasium by invoking the “How Long, Not Long” set-piece he would later use when he spoke from the steps of the capital at the end of the final march in Selma, Alabama on March 25, 1965. He then continued with eight consecutive lines of “I have a dream” before also ending with the “Let Freedom Ring” passage made famous when he spoke on the Mall of Washington on August 28, 1963.

This speech in Rocky Mount is part sermon, part mass meeting, and part civil rights address. The rare and inspired delivery of all of his most dramatic endings and the unusual overlap of genres makes this address one of the most unique and historic speeches ever delivered by the twentieth century’s greatest orator.

Now for the first time, this historic speech can be heard.

Audio Tape

This recording of the speech was digitally restored by one of the world’s leading audio archivists. Philadelphia’s George Blood, a man who has been digitizing music for the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Boston Symphony (among many others), restored this tape to its best original levels to present the speech as it sounded in 1962. George has written the guide for audio restoration used today by the Library of Congress. Absolutely no overdubs, edits, or changes have been made to this recording in any way.

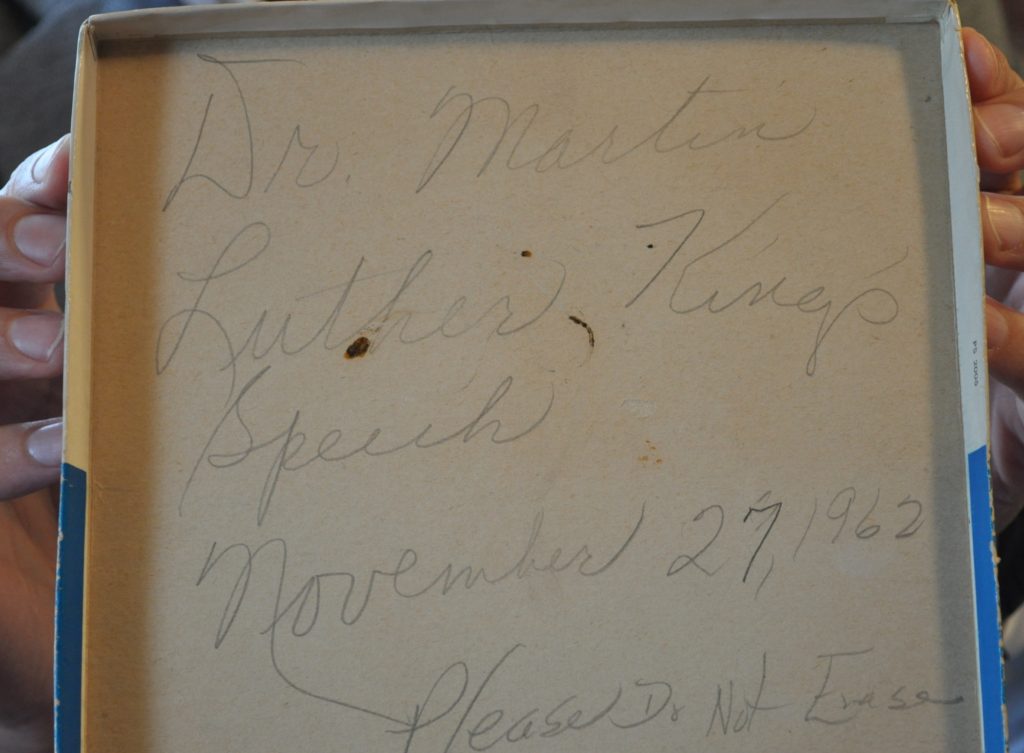

The original speech was recorded on a 1.5 millimeter acetate reel-to-reel tape. After being recorded, the tape was stored in an attic for 38 years and then spent another 12 years in a closet in the Rocky Mount city offices. Once the tape  was located at the Braswell Memorial Library in Rocky Mount in September of 2013 (with the assistance of Traci Thompson), its contents were carefully confirmed by playing the tape through Skip Elsheimer’s best reel-to-reel player. Somehow the tape miraculously survived in excellent condition through all these years. The tape was then hand delivered to George Blood Audio in Philadelphia who digitized and then restored this historic speech. George’s expertise was essential. He passed the tape through his best reel-to-reel player, and simultaneously took both tracks from the tape. He did not just simply

was located at the Braswell Memorial Library in Rocky Mount in September of 2013 (with the assistance of Traci Thompson), its contents were carefully confirmed by playing the tape through Skip Elsheimer’s best reel-to-reel player. Somehow the tape miraculously survived in excellent condition through all these years. The tape was then hand delivered to George Blood Audio in Philadelphia who digitized and then restored this historic speech. George’s expertise was essential. He passed the tape through his best reel-to-reel player, and simultaneously took both tracks from the tape. He did not just simply  digitize the speech by transferring it from one medium to another. Merely playing the tape would leave any transcript filled with question marks and guess words. On its own, the whole tape sounds muddy and unclear and several sections are almost wholly inaudible. George “cleaned” the overall sound, slowed down sections (and sped others up) so that now every word of this fifty-five minute speech can be heard as it did the day the speech was delivered. Listeners can hear individual audience members seated on stage as well as Dr. King rapping his knuckles across the podium to emphasize his points. This audio version of the speech is the only original copy of this historic speech that is known to have survived. This complete process, as well as the creation of the fully accurate transcript (and fully annotated transcript) was overseen by Dr. Jason Miller, Professor of English at North Carolina State University.

digitize the speech by transferring it from one medium to another. Merely playing the tape would leave any transcript filled with question marks and guess words. On its own, the whole tape sounds muddy and unclear and several sections are almost wholly inaudible. George “cleaned” the overall sound, slowed down sections (and sped others up) so that now every word of this fifty-five minute speech can be heard as it did the day the speech was delivered. Listeners can hear individual audience members seated on stage as well as Dr. King rapping his knuckles across the podium to emphasize his points. This audio version of the speech is the only original copy of this historic speech that is known to have survived. This complete process, as well as the creation of the fully accurate transcript (and fully annotated transcript) was overseen by Dr. Jason Miller, Professor of English at North Carolina State University.

Historical Context (A Brief Overview)

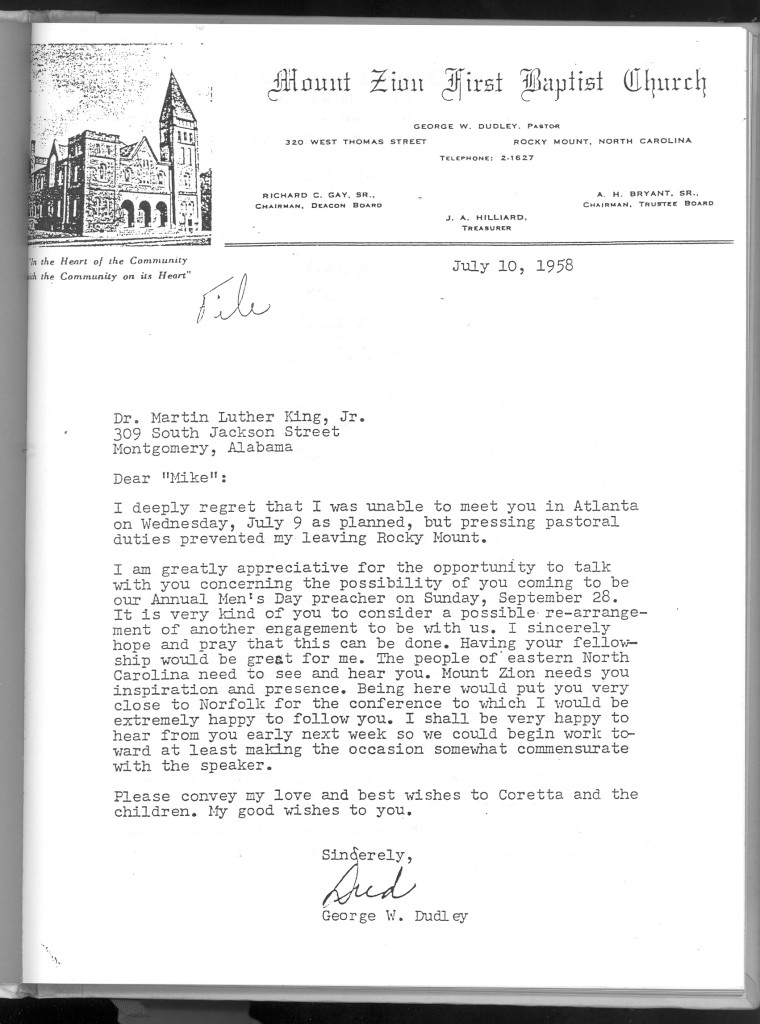

George Dudley, the pastor at St. John AME Zion Church from 1958-1986, had invited King by phone to speak in Rocky Mount as early as February 21, 1958. Soon after, Pastor Dudley wrote that he was trying “to get some new life in our local chapter of the NAACP and get into our people a sense of Citizenship.” He had planned to hold a mass meeting for either March 19, 20, or 21. King was unable to commit to any of these dates in 1958. Over four years later, on November 14, 1962, Pastor Dudley (serving as President of the Rocky Mount Voters and Improvement League), announced that Dr. King had accepted his invitation to speak in Rocky Mount on Tuesday, November 27th at 8:00 pm. Dr. King came (as his father had before him) because he and Rev. Dudley had known each other since childhood as they grew up in the same Atlanta neighborhood. In fact, Rev. Dudley had known Dr. King so long that he affectionately referred to him by his childhood name of “Mike” when they spoke or corresponded by letter (see letter).

Just before this speech, King had completed a failed campaign in Albany, Georgia, that occupied much of his energy throughout 1962. King arrived in Rocky Mount after speaking recently in Sasser, Georgia, on November 16, 1962 to commemorate the terrorizing burning of two black churches that had served as campaign headquarters for trying to secure long overdue voting rights for African Americans. Rightly fearing threats from the local KKK, King was picked up at the Raleigh airport in a C.C. Stokes Funeral Home hearse to conceal his whereabouts and driven to Rocky Mount in this clandestine fashion to avoid being easily located.

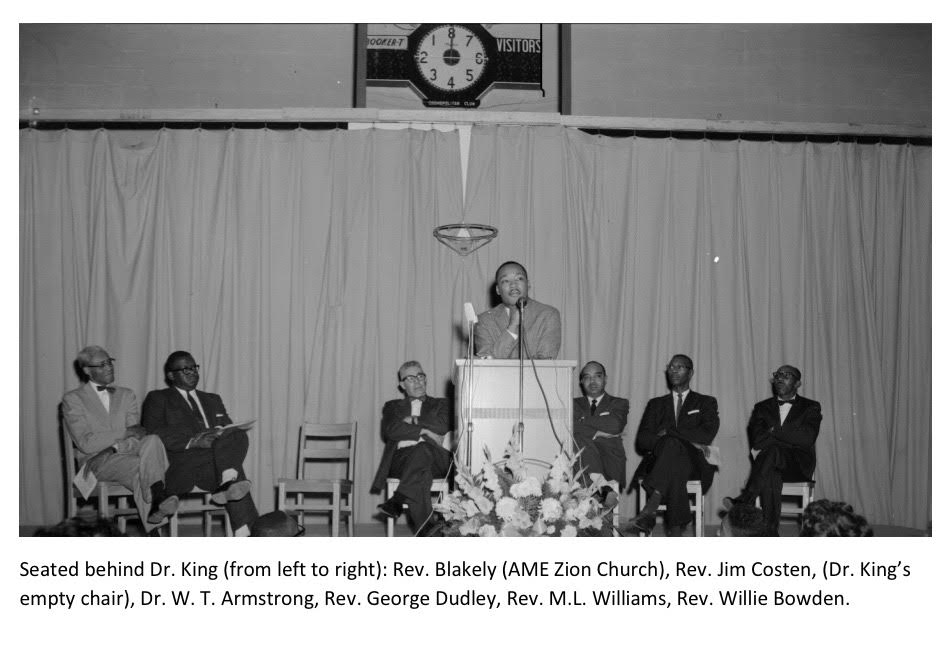

After delivering his speech in Rocky Mount, Dr. King ate a meal at Pastor Dudley’s home prepared by future City Councilwoman Helen Gay. Again fearing violence from area white supremacists, the then caterer Helen Gay had carefully taken precautions to avoid being discovered by anyone listening in on the phone lines. When Dr. King arrived at Pastor Dudley’s home, Helen Gay phoned her friend Martha Stith speaking to her using a predetermined code. When Martha heard, “The Blackberry pie is ready,” she knew her small group of friends should drive over for dinner because that phrase meant King himself had just arrived. Sometime during his visit (perhaps on Friday), Dr. King also attended a meeting at the St. John AME Zion Church in Rocky Mount (located on the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Goldleaf Street). With the doors to Booker T. Washington Gymnasium opening at 7:00 for the free and open to the public 8:00 event, over 1,800 people heard Dr. King greeted briefly by Mayor William (Billy) Harrison. Wisely fearing repercussions, Harrison (who was mayor from 1962-64) had nonetheless agreed to introduce King at his own wife’s urging. The mayor soon left the event. (Family fears were confirmed the next year when a cross was set on fire in the front lawn of the Harrison’s home in response to the mayor leading the way to integrate the city library and public swimming pool. This cross was discovered by Billy’s wife Kate and daughter who were home alone.) Before leaving, the mayor announced to the crowd that the “two races” in his city “have lived, worked, and progressed together in an atmosphere of mutual understanding and respect.” He asserted that this had not been “by accident nor because of the Supreme Court decision, but as the result of long-term efforts on the part of the city leaders of both races in trying to anticipate and fulfill the needs of all our people.” He gestured toward his well-placed fears when he ended his remarks by saying: “In these troubled times when other cities and other places have been torn with strife and violence and hatred, I hope we in Rocky Mount may be able to continue our progressive course without force, sit-ins, picketing, or boycotting, but with the understanding, goodwill, and faith and sincerity in the true spirit of Christianity.” These remarks were sincere as the mayor continued to take the lead on these issues in the years to come to help integrate the city in many areas including its public schools. After being welcomed by the mayor, Dr. King was formally introduced by Pastor Dudley. These two men were joined on the stage that evening by others (see above) including Dr. W. T. (Wiley) Armstrong who was serving as the vice-president of the Rocky Mount Voters and Improvement League. Moreover, a United Choir Guild of over 100 voices (directed by William T. Grimes) supplied music at the event. Many of these members were formally dressed in white robes. When Dr. King ended his fifty-five minute speech, the local newspaper reported that Dr. King received a “thunderous standing ovation.”

After being welcomed by the mayor, Dr. King was formally introduced by Pastor Dudley. These two men were joined on the stage that evening by others (see above) including Dr. W. T. (Wiley) Armstrong who was serving as the vice-president of the Rocky Mount Voters and Improvement League. Moreover, a United Choir Guild of over 100 voices (directed by William T. Grimes) supplied music at the event. Many of these members were formally dressed in white robes. When Dr. King ended his fifty-five minute speech, the local newspaper reported that Dr. King received a “thunderous standing ovation.”

While King had traveled to North Carolina before, he had not ever visited Rocky Mount. In between revising his sermons for the book Strength to Love, King soon returned again on a brief tour through the northeastern part of the state. On December 20, 1962, he spoke before 500 people in the armory at Edenton, North Carolina.

November 27, 1962 places King’s use of “I have a dream” nine full months prior to its use at the Mall on Washington D.C. on August 28, 1963. Having just completed the failed campaign in Albany — and right before the beginning of the successful project C (“C” standing for confrontation) still to come in the spring of 1963 in Eugene “Bull” Connor’s very own home of Birmingham, Alabama—King’s determined vision shows his resilience and optimism during one of the lowest points of his career.

While select scholars have long known that Dr. King used the refrain “I have a dream” at least two months before the March on Washington when he spoke in Detroit on June 23, 1963, this audio tape from Rocky Mount, North Carolina conclusively confirms that Dr. King had been using the refrain much earlier. The trajectory of this development reveals several things about what has come to stand as Dr. King’s most visible ideal.

First, Rocky Mount, North Carolina is now the site of a historical moment in our nation’s history. Rocky Mount, North Carolina, is the place where Martin Luther King’s first documented use of his iconic phrase “I have a dream” was delivered. This phrase serves as the basis of the century’s most recognizable speech. By 2008, over 97% of American teenagers recognized its words.

Second, we now have access to the complete audio recording, transcript, and annotated transcript of one of Martin Luther King’s most unique, lengthy, relevant, and inspiring speeches. Hearing a speech few have even read deepens the historical record of Dr. King’s dream and provides remarkable avenues of understanding for both scholars and the general public. The accuracy that is provided by the actual recording cannot be understated.

Third, while Dr. King’s incantatory delivery on the Mall of Washington made his dream seem spontaneous, it was actually invoked before August 28, 1963. In addition to these two iterations, we also know King ended a speech on June 23, 1963 with “I have a dream.” He refined and altered the refrain on each of these occasions before his most famous address. Understanding these alterations and their origins helps to amplify their history, effectiveness, and purpose.

Fourth, Dr. King’s dream is held together by oral poetry. King not only illuminated the political ideals of the American dream and the prophetic nature of scripture when he spoke the words “I have a dream,” the repeated and well-measured uses of anaphora also reveal that his dream was literally poetic. In fact, Dr. King had been revising this same speech “Facing the Challenge of a New Age” since he first delivered it on August 11, 1956 in Buffalo, NY.

In that speech, long considered the thematic precursor to his “I Have a Dream” address in Washington, new research reveals that Dr. King ended his comments by rewriting (line by line) a famous poem by Langston Hughes entitled “I Dream a World”:

“I Dream a World”

I dream a world where man

No other man will scorn,

Where love will bless the earth

And peace its paths adorn.

I dream a world where all

Will know sweet freedom’s way,

Where greed no longer saps the soul

Nor avarice blights our day.

A world I dream where black or white,

Whatever race you be,

Will share the bounties of the earth

And every man is free,

Where wretchedness will hang its head

And joy, like a pearl,

Attends the needs of all mankind-

Of such I dream, our world! by Langston Hughes, 1941

This means that the poetry we recognize when we hear King repeat “I have a dream” is not merely the effect of a gifted speaker but rather the choice of man who knew and revered poetry so much that he memorized it. More than simple repetition, poetry is the thread that repeats in “I have a dream” and keeps the metaphor lingering in listeners’ minds. The themes of this speech, transformation and integration, are reinforced by King’s actual rhetoric as he simultaneously transforms and integrates ideas from scripture, the American Dream, and Hughes’s poetry. These are the three threads Dr. King stitched together to form his famous refrain.

While the first two of these threads has been well understood, the connection to Hughes is brand new. For the very first time, the trajectory of Dr. King’s revisions to his dream confirms Langston Hughes’ own personal beliefs—and the suspicions of many scholars— that King’s famous “I have a dream” refrain was linked directly to Hughes’ poetry. This confirmation significantly deepens the historical record of these two American icons.

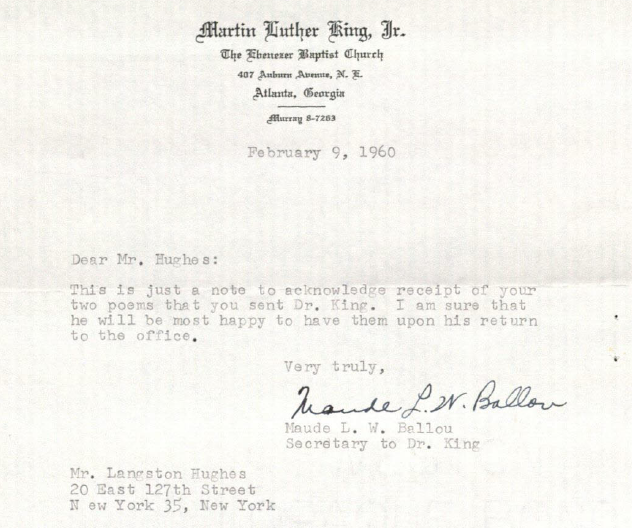

Born in 1902, Langston Hughes was one of the leading figures of the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920-30s that celebrated the culture and artistry of African Americans in and around Harlem, NY. During his career in the public eye from 1956-1968, Dr. King invoked no less than seven of Langston Hughes’ poems in his speeches and sermons (often reciting Hughes’s poems from memory). As contemporaries, the two men knew each other and exchanged letters.

In fact, Hughes died in May of 1967, less than a year before King was assassinated. As he prepared for the surgery from which he would soon die from, one of Hughes’ final handwritten letters was sent directly to Dr. King.

King always understood the power of current events. Playing off the final image of Hughes’s most famous poem “Dream Deferred,” Dr. King delivered one of his most powerful and personal sermons “Shattered Dreams” from his pulpit three weeks after another image from Hughes’ famous poem had become the source of inspiration for the immediate and long-staying Broadway hit “A Raisin in the Sun.”

“Dream Deferred”

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore-

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over-

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Langston Hughes was the leading African American poet of Dr. King’s generation. Despite this reverence, Hughes was also overtly labeled a communist subversive. This made overtly invoking his ideas a challenge for Dr. King when he spoke in public.

Starting then in November of 1962, Dr. King began to stitch together his own dream by integrating numerous ideas across a wide range of sources. This act of integrating sources allowed his speeches to model the social integration he was calling for across the nation on all levels.

In addition to other sources, this speech in Rocky Mount confirms that the origins of Dr. King’s dream can also be traced back to the poetry of Langston Hughes. In 1956, when Dr. King was first attracted to Hughes’s poem “I Dream a World,” he focused on the poem’s image of a new world: when he revised this speech in 1962, he held fast to the idea of the dream by stitching together the political idea of the American dream and the prophetic stance of vision with the poetic ideals he’d first encountered in the poetry of Langston Hughes.

Why has the connection to Hughes been so hard to document?

Because of his controversial reputation, Dr. King never overtly referenced the name or ideas of Langston Hughes between 1960 and 1965. These were the years in which the Communist label resulted in the most effective attacks against King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. However, Hughes’s ideas appear throughout the time that immediately precedes and follows this era in which King was most in the public eye. Between 1960 and 1965, King simply personalized them and avoided directly naming Hughes or his poems.

This speech confirms that Dr. King played a dangerous and high stakes game when he was dreaming. By rewriting rather than quoting Langston Hughes’ words, Dr. King simultaneously invoked his ideas by exalting the cultural roots of African Americans while at the same time outwitting those in power who would have attacked and discredited King for embracing an incendiary political stance ascribed to Hughes and his poetry. This combination of deep cultural pride and subversiveness has often been overlooked in Dr. King’s speeches.

This tension helps us better understand the political climate of 1962. Dr. King riffed on the words of a black poet who stood simultaneously as the embodiment of the cultural values of African Americans even as he represented the nation’s greatest fears about Communist subversion. From the lips of Dr. King, poetry, prophecy, and politics worked together to move the nation and form the basis of our nation’s most recognized speech.

Thanks to all who worked to bring this work to light.

I have sent this website to my son with the challenge to share with his friends and

his generation even as we are reliving these very situations today.

We still have much work to do!

This coming Tuesday 4 April 2017, NC State is hosting a reading at the Alumni Bell Tower of Dr. King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech given 50 years ago in New York. His prophetic vision for America and the world are even more true today than at that time, and the fact that our nation still needs to embrace the prophecy is shaming on us all. There is a literary richness as well as moral prophecy that comes out of those ’60’s writings and speeches that informs us of our future direction as individuals and as a country. We would do well to pay closer attention before another 50 years creeps up on us.